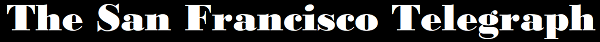

With Keir Starmer replacing Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the UK Labour Party, and Bernie Sanders suspending his campaign in the US, the wave of democratic socialism, which seemed capable of reshaping both the US and UK, has receded.

There are four major reasons why: the limits to which such movements can broaden their base, timing and events, ideological inflexibility in the face of criticism, and attempts to weaponize PC identity politics along with their more mainstream colleagues, which were undermined in the public eye by contradictions like the scandal around anti-Semitism in the UK Labour Party, and the obnoxious behaviour of some of the ‘Bernie Bros’ in the US.

In late 2019, the opposition Labour Party in the UK, led by a self-identified democratic socialist, was running level with the government in the polls. A few months later in the United States, a self-identified democratic socialist leading a fervent, well-funded and well-organised grass-roots movement seemed poised to capture the Democratic nomination for president, and was performing well in hypothetical match-ups in key states against the incumbent. For a moment, it looked like both the US and UK might be transformed by socialist-influenced administrations.

Jeremy Corbyn was elected as leader of the UK Labour Party in September 2015. He supported a higher rate of income tax for the wealthiest in society, advocated for re-nationalisation of public utilities and the railways, a less interventionist military policy, and reversals of austerity cuts to welfare and public services. In education, he put forward a policy to scrap all tuition fees. When asked if he regarded himself as a Marxist, Corbyn responded by saying: “That is a very interesting question actually… I haven’t really read as much of Marx as we should have done.” Similarly, defending John McDonnell’s statement that there is “a lot to learn” from Karl Marx’s book Das Kapital, Corbyn described Marx as a “great economist.” In the 2017 general election, Labour increased its share of the vote. The result was so impressive that it forced the Conservatives to form a minority government. As late as August of 2019, Labour was running about even with the Conservatives in the polls. In October, Prime Minister Boris Johnson called for an election, to be held just before Christmas. Labour received its lowest number of seats since 1935. The result led to Corbyn’s announcement that he would stand down as Labour leader. Now, with Keir Starmer’s election as leader, the party is set to return to the center.

In the US, former Vice President Joe Biden was the nominal front-runner for the Democratic nomination for all of 2019. A string of average debate performances, the entry of Mike Bloomberg into the race, the division of the center lane as the party cast around for an ideal candidate, all combined to allow the democratic socialist, Bernie Sanders, already well financed and well organised, to emerge as the frontrunner, seemingly poised with irresistible momentum, after early victories, to gain a huge haul of delegates on Super Tuesday. As late as 24 hours before that major string of contests, he was leading in delegate-rich states, and seemed about to rack-up something close to an insurmountable lead. A last-minute coalescing of the establishment around Biden turned the tables, with Biden now the presumptive nominee. The democratic socialist, having pushed centrist Hillary Clinton hard in 2016, and having reached the same limits of coalition-building as then, dropped out last night.

Either Corbyn or Sanders winning power would have been socially transformational; especially in the UK, where the government is not burdened by the Senate filibuster. Either major economic powerhouse may have had the government take charge of the means of production, in some approximation of a command economy. The US would have seen an attempt at a multi-trillion-dollar reshaping of the healthcare system – one sixth of the economy – to the eradication of all private healthcare. Both would have seen a once-in-several-generations redistribution of wealth.

Also on rt.com Sanders sinks again: The populist Democrat departs the race just when his message was most relevant

They failed for several reasons. The first is that, with Sanders vs Biden being, in many ways, Sanders vs Clinton redux, we are seeing again the limits of movement politics, the extent of expansion, the pre-eminence of the establishment, and the ability of the establishment to move with facility and cohesion to supervene at critical junctures. Secondly, ideological obstinacy is a double-edged sword. As leaders of pure ideological movements, the likes of Corbyn and Sanders often have a blind spot where they confuse inflexibility with authenticity. In Sanders’ case, this manifested itself as an inability to recognise any danger in failing to qualify his praise of aspects of the Castro regime, at a critical time when vast numbers of observers and voters were becoming increasingly anxious about Sanders’ rise. Thirdly, such movements are vulnerable to, and not particularly agile at, adapting to major events: in Corbyn’s case, Brexit became a complicating and overshadowing saga, which he responded to in an ambivalent way. When it became the dominant issue, requiring an emphatic response, movement politics became a secondary priority to the public. In Sanders’ case, ideological purity became secondary to the chief consideration registered by Democratic voters in polls: the need to defeat Donald Trump. Lastly, these progressive movements have hypocritical contradictions: an undertow of anti-Semitism in the UK Labour Party, the occasional misogynistic tendencies of some of the ‘Bernie-Bros,’ combined with ‘woke’ identity politics that can, and have attempted to, vindictively suppress opposing views through ‘cancel-culture.’

The vast numbers who follow Bernie Sanders will not disappear; but Sanders has been a singular figure: unerring in his message, and amassing support over decades. There is no obvious successor. The UK Labour Party, languishing under Corbyn, and alienating its working-class base with identity politics, will not be returning to the far-left for the foreseeable future. The notion of a Transatlantic ascendancy of democratic socialism, radically reshaping the US and the UK, seemed a realistic proposition for a whole year. That high tide has now receded.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!

NEWS5 months ago

NEWS5 months ago

NEWS5 months ago

NEWS5 months ago

NEWS5 months ago

NEWS5 months ago

WAR5 months ago

WAR5 months ago

FINANCE5 months ago

FINANCE5 months ago

INVESTMENTS5 months ago

INVESTMENTS5 months ago

FINANCE5 months ago

FINANCE5 months ago